An American accent speaks volumes about these Romans at the far edge of empire was the headline of a Times article about the film of The Eagle of the Ninth this week which explores the modern parallels. (Shame they spelled Rosemary’s name wrong. Even bigger shame that they have not corrected it, despite my writing to them!). The article’s author writes:

An American accent speaks volumes about these Romans at the far edge of empire was the headline of a Times article about the film of The Eagle of the Ninth this week which explores the modern parallels. (Shame they spelled Rosemary’s name wrong. Even bigger shame that they have not corrected it, despite my writing to them!). The article’s author writes:

The Romans’ attitudes (including Marcus played by American Channing Tatum) are contrasted with those of Esca, a Celtic slave, played by Jamie Bell, whose distance from his master is emphasised by his voice — Bell speaks in his native Teesside accent for the first time since Billy Elliot, his breakthrough movie.It seems a credible scenario. A well-intentioned modern army marches off convinced that it can impose its superior culture on a distant country. But within months, its leaders are tragically disabused and, among mountains far from home, the troops face an implacable foe and, ultimately, bloody defeat.

If film lovers leaving The Eagle of the Ninth find their thoughts turning to events in Iraq or Afghanistan, its director, Kevin Macdonald, will have achieved at least one of his goals. For though it tells the tale of a Roman legion that is said to have perished in Scotland, his new film is just as concerned with today’s events in faraway lands. To ram the point home, the American actors Channing Tatum and Donald Sutherland are cast at the head of the occupying Roman force.

“It was always my concept for this film that the Romans would be Americans,” says Macdonald.

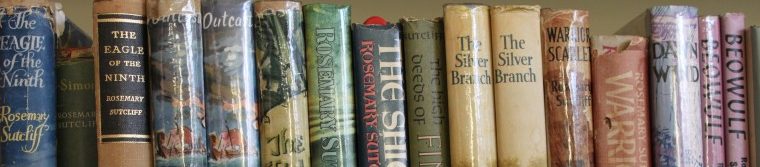

“That was my first idea about the movie and it still holds up whether or not we had any money from America, that would have been my approach.” The Eagle of the Ninth is based on a 1950s novel by Rosemary Sutcliffe and stars Tatum as Marcus Aquila, an idealistic Roman soldier, whose uncle, Aquila, played by Sutherland, epitomises the confidence of the occupying army.

“It’s a film is about a guy who believes wholeheartedly in the values of Rome, and believes everyone else must want to become a part of the great family of Rome,” says Macdonald, who has completed the director’s cut of the movie.

“Marcus thinks, ‘It would benefit them so much — can’t they see it is the only way to live their lives?’ He comes to realise there are other value systems, other people have a claim to honour in the same way that he as an American — or a Roman — can claim honour. This is a film which is some way reflects the some of current anxieties and the political questions that we all have.”

The Romans’ attitudes are contrasted with those of Esca, a Celtic slave, played by Jamie Bell, whose distance from his master is emphasised by his voice — Bell speaks in his native Teesside accent for the first time since Billy Elliot, his breakthrough movie.

The same linguistic trick is accentuated as the Ninth Legion heads beyond Hadrian’s Wall. The Romans encounter the Seal People whose Gaelic language is unintelligible to their uninvited guests, and their world and values remain a mystery to the invaders.

By casting Mahar Ramin as the Seal Prince, Macdonald adds the promise of good box office from a rapidly- rising star. Ramin, lauded at the Baftas for his role in The Prophet, voted best foreign language film, “brings a humanity, a roundedness, to even the most evil moments, the difficult, dark decisions that a person makes”. Macdonald, 42, believes his film stands squarely in the Hollywood tradition of Ulzana’s Raid, a Burt Lancaster vehicle or A Man Called Horse, starring Richard Harris, both 1970s Westerns that carried a fierce anti-war message about the conflict in Vietnam.

“That’s what we are doing — not simply reflecting on the Afghanistan or Iraq wars, but a sense of cultural imperialism,” he says. “Those films dealt with torture and maltreatment of prisoners, but in the context of Indians. The parallel is definitely there, and it is part of what you would want the audience to take away from the film. But it is not necessarily literal. Literalism is very often the death of films.”

The US is not the only country to have established a modern empire. Over generations, millions of Scots felt the benefit of the British Empire. So why not British actors attacking the Seal People? “Britain isn’t a force any more, we aren’t cultural imperialists. That just didn’t seem the right way to go.”

Macdonald, who was brought up near Loch Lomond and cut his teeth as a documentary maker, has been widely praised for the attention to detail he brought to State of Play and The Last King of Scotland. Despite the absence of clear historical data, to deliver the discomfort of the Roman soldier he filmed in Argyllshire and Wester Ross in October and November in the belief that “Scotland looks best when it’s brown, yellow and dreich”. For the cast it was “quite a trial” but the effect is “to make you feel what it was like to have no shoes on, and to be in that landscape in that climate”.

The result, he believes, is a film with an epic dimension — without the excess of Gladiator — but in the sense of “men alone in the landscape, and the unfamiliarly of the world they have come across”.

(Eagle of the Ninth will be released in September)

Source: here ; and note that The Times originally as in this copy text spelt Rosemary Sutcliffe (sic) wrongly. There should be no ‘E’.